Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) is a bacterial infection that can cause life-threatening symptoms in people with weakened immune systems. People who have healthy immune systems can also be infected but their symptoms are not usually serious. In people with advanced HIV disease, MAC usually causes disease in the liver, spleen, and bone marrow.

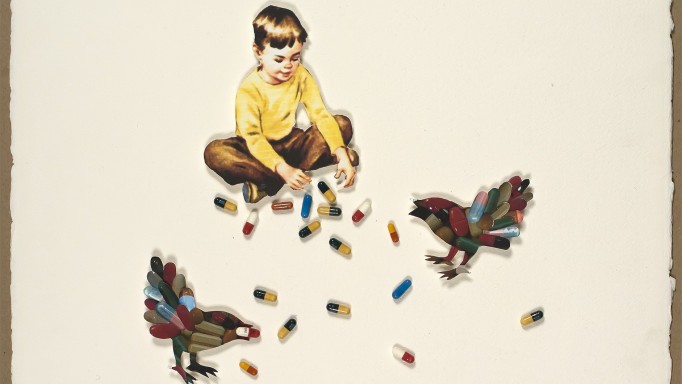

There are two MAC bacteria—M. avium and M. intracellulare—and both can be found virtually anywhere in the environment. They live in water, soil, food, bird droppings, and many animals. As a result, it is difficult to avoid coming into contact with them. If infection occurs, it is usually through water or food or the lungs. It cannot be passed from person to person.

However, MAC disease is preventable. One of the best ways to prevent it is to avoid CD4 counts from dropping below 100 by starting potent HIV treatment. In people whose CD4 counts do not respond adequately, preventive drugs are taken. MAC generally occurs in 2 out of 5 people with HIV and low CD4 counts.

What are the symptoms, and how is it diagnosed?

People who are most at risk for MAC disease are people with HIV whose CD4 counts are below 50. Having had an earlier opportunistic condition also increases the risk, as well as having a viral load above 100,000.

Fever is the main symptom of MAC, along with night sweats, loss of appetite, chills, weight loss, muscle wasting, abdominal pain, tiredness, and diarrhea. MAC can also enlarge the liver, spleen, and lymph nodes. If it’s in other parts of the body, which is common, other symptoms can occur such as joint pain.

If HIV treatment is started while a latent MAC infection is present, a condition called immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) can occur, especially when CD4 counts are below 200 and response to HIV treatment occurs quickly. IRIS increases inflammation in the body as the new HIV meds help the immune system gain control of infections like MAC. Some providers use corticosteroids for a short time to help prevent and/or ease these symptoms.

To diagnose MAC, fluid or tissue samples are collected from the blood, lymph nodes, bone marrow, etc. and sent to a lab for testing. The bacteria must be “grown” in test tubes, which can take about a week. If MAC is suspected, treatment is often started before a diagnosis is confirmed.

How is it treated?

MAC is treated using antibiotics. As with HIV, in which three drugs are used to help prevent resistance and keep viral load undetectable, MAC must be treated with more than one antibiotic to maintain control over the bacteria.

It can take 2–8 weeks for a person with MAC to begin feeling better after starting treatment. Because of this, MAC is often treated in a hospital, where resources are readily available to help manage symptoms, such as weight loss, fever, and dehydration.

Almost always, MAC treatment includes the following:

- Clarithromycin (Biaxin): This antibiotic is extremely effective against MAC, while an alternative is azithromycin (Zithromax). Clarithromycin has been more fully studied and appears to result in clearing MAC more rapidly from the blood. However, azithromycin is considered to be an excellent substitute, when drug interactions or side effects are possible concerns. Both drugs can cause nausea, headaches, vomiting, and diarrhea and increased liver enzymes. Experts recommend testing blood samples to determine whether the bacteria are susceptible to either antibiotic.

- Ethambutol (Myambutol): This antibiotic is active against MAC, but not powerful enough on its own. As a result, it is almost always combined with either of the two above. Side effects include nausea, vomiting, and vision problems.

To help prevent drug resistance and increase the potency of MAC treatment, a third and sometimes fourth antibiotic are recommended by doctors. Rifabutin (Mycobutin) is effective, but may cause drug interactions, particularly with protease inhibitors or NNRTIs used to treat HIV. Other options include injected amikacin (Amikin) and streptomycin or fluoroquinolones such as levofloxacin or moxifloxacin.

If a person with HIV is diagnosed with MAC, he or she may need to stay on antibiotics in order to prevent MAC from returning especially if their CD4 count stays below 100. If HIV treatment increases the CD4 count to above 100 for at least six months, MAC preventive treatment may be stopped.

Pregnant women should not take clarithromycin. Azithromycin is recommended in this case, and pregnant women with disseminated MAC should be treated with azithromycin plus ethambutol and continue this treatment as secondary prevention.

How is it prevented?

As mentioned above, it is very difficult to prevent coming into contact with the bacteria. In turn, most health care experts recommend starting preventive treatment when the CD4 count falls below 50. When the CD4 count increases to and stays above 100 for at least three months, preventive treatment may be stopped. However, it must be restarted if the CD4 count falls below 50 again.

The same two antibiotics used for treating MAC disease are also used to prevent it—clarithromycin and azithromycin. When they are taken correctly, the risk of developing MAC is decreased by about 70%. In other words, they are often effective but not always.

If MAC disease occurs while using these preventive antibiotics, it’s possible that the bacteria have developed resistance to the drugs. If MAC becomes resistant to clarithromycin then it also becomes resistant to azithromycin, and vice versa. Most experts believe that the benefits of preventive treatment outweigh the potential risks of drug resistance.

Both antibiotics cause similar side effects. To prevent MAC, clarithromycin must be taken once a day, while azithromycin needs to be taken once a week.

Are there any experimental treatments?

If you would like to find out if you are eligible for any clinical trials that include new therapies for the treatment or prevention of MAC, visit ClinicalTrials.gov, a site run by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The site has information about all HIV-related clinical studies in the United States. For more info, you can call their toll-free number at 1-800-HIV-0440 (1-800-448-0440) or email contactus@aidsinfo.nih.gov.

Last Reviewed: October 23, 2018